You are hereBlogs / WcP.Watchful.Eye's blog / What goes up... Space junk: how to clean up the Space Age's mess; > 4 million pounds of trash orbiting Earth

What goes up... Space junk: how to clean up the Space Age's mess; > 4 million pounds of trash orbiting Earth

(quote)

The Trouble With Trash

It's been 53 years and over 4,500 launches since the dawn of the space age, and Earth's orbit is a junkyard. Our orbit is littered with spent rocket stages, lens caps, broken-up satellites, frozen urine, the odd glove, bits of foil, and the tool kit dropped by astronaut Heide Stefanyshyn-Piper during a spacewalk in 2008. You name it; the low Earth orbit has probably got it.

Millions of pieces of this space debris orbit the globe at break-neck speeds, and the spacecraft that pass through orbit are in jeopardy from even the smallest objects. But while the problem is evident, the solution remains elusive. Will Earth's orbit forever resemble a scene from WALL-E? Many scientists have now turned their attention to cleaning up the clutter.

Every satellite that goes up to orbit is the pride and joy of some company, lab, or nation. But once it has outlived its purpose, it's nothing but junk.

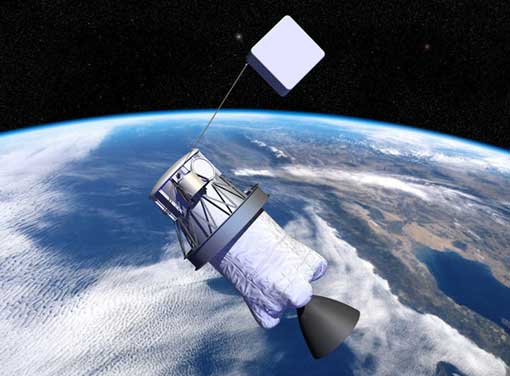

Attaching a hi-tech kite-tail to satellites might seem too simple to work. But electrodynamic tethers could provide a low-cost, lightweight method of debris removal. Best of all, they operate without fuel. Tethers take advantage of the Earth's magnetic field, interacting with the ionosphere via 3-mile-long wires to produce a drag effect, pulling defunct satellites down to lower orbits until they burn up in the atmosphere.

Tethers Unlimited Inc. has a working prototype called the Terminator Tether that could de-orbit large satellites in a matter of months after being deployed. Pictured is an artist's concept of NASA's ProSEDS tether, a variation on this model designed as a source of propulsion.

By far the greatest tool for preventing collisions is careful monitoring. NASA and the Department of Defense currently track over 21,000 objects using ground- and space-based surveillance systems, following pieces as small as 2 inches in diameter.

This detection will soon be twice as sensitive; the U.S. Air Force "pathfinder" satellite expected to launch this year will be the first-ever satellite devoted solely to tracking debris. It should help fill in holes in the data, and hopefully prevent collisions like the much-publicized crash of two satellites in 2008.

The Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) satellite, shown here docking above the Space Shuttle Challenger, was another important asset, having tracked debris for six years before being decommissioned in 1990.

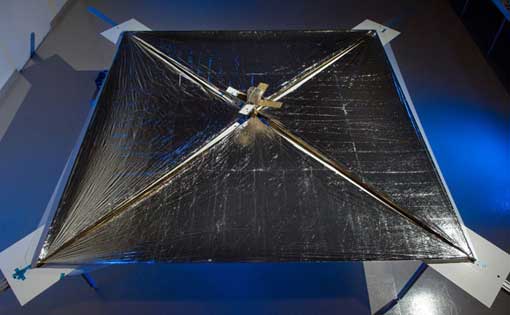

Another device that could speed up the decay of orbiting clutter is the solar sail. Proponents of this technology suggest that a folded-up sail could be attached to satellites, rocket stages, or any other piece of space-going technology. When that technology reaches the end of its working life, the sail would pop open.

Once deployed, these carbon fiber sails would harness solar winds to propel objects back into the Earth's atmosphere. In March of 2010, a working prototype called the Cubesail was revealed by the University of Surrey, and is expected to be tested in a demonstration mission next year. Further afield, researchers say the Cubesail could be sent into orbit to remove existing debris.

NASA ordered the space station to change position Wednesday evening to avoid a fragment from a communication satellite that was destroyed in a high-speed collision three years ago.

Thrusters on a docked Russian supply ship were fired to move the orbiting lab out of harm's way. But a computer error caused the thrusters to malfunction and the space station did not reach the desired altitude. NASA officials said the space station and its six residents were safe despite their lower-than-intended orbit.

Space station commander Sunita Williams and Japanese astronaut Akihiko Hoshide wasted no time installing jumper cables outside the orbital outpost that's been their home for the past four months. Their objective was to isolate a suspect radiator to help determine whether that is the source of the ammonia coolant leak, and deploy a spare radiator to bypass the troublesome section.

Engineers theorize that bits of space junk may have penetrated the radiator or part of its system. Another possibility is that the 12-year-old equipment simply cracked.

The radiators are needed to dissipate heat generated by electronic equipment aboard the space station. Toxic ammonia is used as the coolant, and the spacewalkers took care to avoid contamination.

In an interview with The Associated Press earlier this week, Williams said the biggest risk is the uncertainty surrounding the leak. "We have a lot of extra procedures just in case things don't go exactly as planned," she said. "But we've dealt with ammonia before."

Thursday's spacewalk provided some deja vu for Williams. In 2007, she retracted the spare radiator being brought into service Thursday.

A small leak was detected in this area in 2007. Spacewalking astronauts added extra ammonia last year to shore up the system, but this past summer, the leakage increased fourfold. At that rate, the affected power channel could be offline by the end of the year.

That's why Thursday's spacewalk was ordered up, even though it comes just two and a half weeks before the departure of Williams and Hoshide. The two are scheduled to return to Earth on Nov. 19, after a four-month mission.

(unquote)

See more at original source...

Related Article: 4 Million Pounds of Space Junk Polluting Earth’s Orbit

Photos courtesy of ESA and NASA