You are hereBlogs / WcP.Story.Teller's blog / 5 May 1862 - Cinco de Mayo. Napoleon III (army 6,000) declared war on Mexico, defeated by General Ignacio Zaragoza (army 2,000)

5 May 1862 - Cinco de Mayo. Napoleon III (army 6,000) declared war on Mexico, defeated by General Ignacio Zaragoza (army 2,000)

(quote)

*update* 2019

Cinco De Mayo 2019: Parties And Events In London

In Mexico, the various factions that fought their civil war had borrowed large sums of money from foreign creditors. The fighting devastated Mexico’s economy, and the country had to suspend payments on its debts. Taking advantage of the relative weakness of the United States during the US Civil War, in December of 1861 the governments of France, Great Britain and Spain landed an allied military force at Vera Cruz to protect their interests in Mexico. Juárez negotiated with the allies and promised to resume payments, and the British and Spanish troops began to withdraw from Mexico in April, 1862.

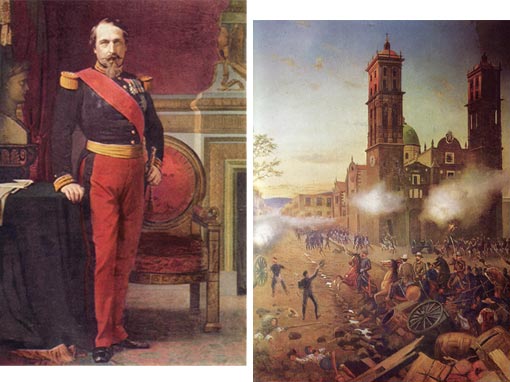

The French, however, did not withdraw and instead sent reinforcements to their troops in Mexico. At the time France was ruled by Louis Napoleon, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. Louis Napoleon was elected President of France, but after the election he proclaimed himself Napoleon III, Emperor of the French (the British referred to him as “the nephew of the uncle”). While negotiations for the Mexican government to repay its debts were ongoing, the French commander, General Charles Ferdinand Latrille, comte (Count) de Lorencez, advanced on Mexico City from Vera Cruz, occupying the mountain passes which led down into the Valley of Mexico. At this point it became clear that Napoleon III planned to turn Mexico into a colony. The French advance was along a route that had been used several times in the past to conquer Mexico, first by the conquistador Hernan Cortes and most recently by US General Winfield Scott during the Mexican War.

France declared war on Mexico, and called on those Mexicans who had fought on the side of the Conser- vative Party in the civil war to join them. Napoleon III planned to turn Mexico into an empire ruled by Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian Josef von Habsburg, the younger brother of the Emperor of Austria-Hungary.

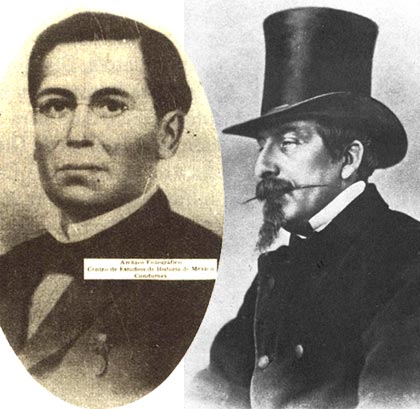

General Charles Ferdinand Latrille, Count de Lorencez, was the leader of the French forces – the Corps Expéditionnaire – which numbered about 7,300 men. He had been their commander for about two months. He was confident of victory. He boldly proclaimed, "we are so superior to the Mexicans in race, organization, morality, and elevated sentiments that as the head of six thousand soldiers I am already master of Mexico." He knew that less than 6,000 US troops – considered poorly trained and disciplined by European officers – had defeated a Mexican Army of 30,000 men under President General Antonio de Santa Anna (Antonio López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón) and taken Mexico City in 1847. General Count de Lorencez had over 1,000 more men than US General Winfield Scott, and the Mexican Army facing the French at Puebla numbered about 6,000 men (the French would later say 12,000) – far less than the army General Scott had defeated.

Furthermore, de Lorencez considered his own French troops far better trained and disciplined than the troops fielded by either the United States or Mexico. In order to make his entry into Puebla as impressive as possible, General Count de Lorencez ordered his troops to apply fresh whitening to their gaiters before the attack.

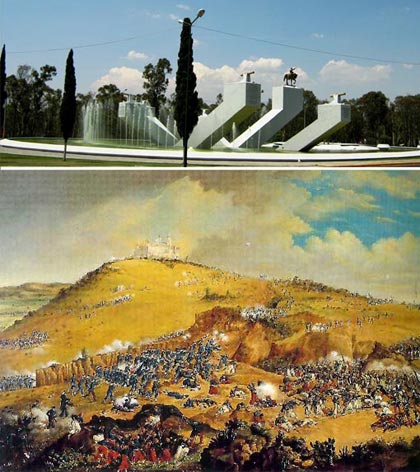

The Mexican Army of the East (Ejército de Oriente), under the command of General Ignacio Zaragoza, took up positions at the town of Puebla (Puebla de los Angeles). This maneuver blocked the French advance on Mexico City. General Ignacio Zaragoza addressed his troops, telling them, "Your enemies are the first soldiers in the world, but you are the first sons of Mexico. They have come to take your country away from you." Zaragoza ordered his commanders – Generals Felipe B. Berriozabal, Porfirio Díaz (José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori), Félix Díaz , Miguel Negrete and Francisco de Lamadrid, to occupy the Cerro de Guadalupe, a ridge of high ground dominating the entrance to Puebla, and the five forts which surrounded the town.

Of the forts, the two most prominent were situated on the Cerro de Guadalupe on either side of the road to Mexico City -- the fort of Loretto to the right, and the fortified monastery of Guadalupe to the left. These were the positions that General Count de Lorencez ordered the Corps Expéditionnaire to attack on May 5, 1862 – Cinco de Mayo.

After a brief artillery bombardment the French began their assault. Caught in a devastating crossfire from the Mexican troops manning the loopholes of the two forts, the French line faltered and then broke. The soldiers of the Corps Expéditionnaire charged the Mexican positions two more times, but each attack was repulsed by the withering musket fire of the Mexican troops. As the beaten French began their retreat, Mexican General Porfirio Díaz, at the head of a troop of cavalry, attacked them. Though badly shot up, the Corps Expéditionnaire was able to retreat in good order. They spent the evening of Cinco de Mayo waiting for an attack which never came. The next day, they began to withdraw back down the road towards Vera Cruz.

When word of the defeat reached Napoleon III, he replaced General Count de Lorencez as commander of the Corps Expéditionnaire with General Elias Frederic Forey, and sent 30,000 troops as reinforcements. The French reaction did little to lessen the shock of the defeat in Europe, and particularly in France. The Mexican Army had proved itself capable of standing up to a first-class European army, and defeating it. The victory of the Cinco de Mayo at Puebla is still celebrated today, 142 years later.

(unquote)

Images courtesy of Nevada Observer and Silversard @ Genuine-Tourist.com

Original Source: Nevada Observer