You are hereBlogs / WcP.Watchful.Eye's blog / Humans drive extinction faster than species can evolve; diversity loss due to destroyed habitats & climate change

Humans drive extinction faster than species can evolve; diversity loss due to destroyed habitats & climate change

Threatened. L: the red squirrel will be lost within the next 20-30 years unless effective action is taken. This poor fella's just heard the news. R: the pine marten. One of England’s rarest, & cutest, mammals.

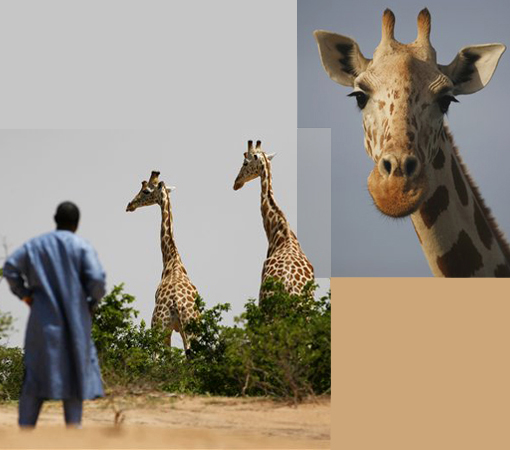

A pair of giraffes nuzzle as they stand in the bush near Koure, Niger. The IUCN lists west African giraffes as an endangered species.

A giraffe from Africa's most endangered giraffe subspecies. Their numbers have quadrupled to 200 since 1996, an unlikely boon experts credit to the impoverished government keen for revenue that has enacted laws to protect them, a conservation program that encourages people to support them, and a rare harmony with humans who have accepted their presence.

Climate change is robbing polar bears of their habitats, & is the greatest threat to their survival.

Polar bear products are used for furs, rugs and taxidermy. Melting sea ice in Arctic will kill thousands of bears in coming years; US says commercial trade must not be allowed to make the situation worse.

L: The great bustard (Otis tarda) is the world's heaviest flying animal. R: The classic reintroduction success story. The red kite has been continually persecuted by humans, to the point of extinction at the end of the 19th century. But by 2009, the English population was up to about 800 pairs. Rivaled only by the large blue butterfly for the title of comeback king.

(quote)

For the first time since the dinosaurs disappeared, humans are driving animals and plants to extinction faster than new species can evolve, one of the world's experts on biodiversity has warned. Conservation experts have already signaled that the world is in the grip of the "sixth great extinction" of species, driven by the destruction of natural habitats, hunting, the spread of alien predators and disease, and climate change. However until recently it has been hoped that the rate at which new species were evolving could keep pace with the loss of diversity of life.

Speaking in advance of two reports next week on the state of wildlife in Britain and Europe, Simon Stuart, chair of the Species Survival Commission for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature – the body which officially declares species threatened and extinct – said that point had now "almost certainly" been crossed. "Measuring the rate at which new species evolve is difficult, but there's no question that the current extinction rates are faster than that; I think it's inevitable," said Stuart.

The IUCN created shock waves with its major assessment of the world's biodiversity in 2004, which calculated that the rate of extinction had reached 100-1,000 times that suggested by the fossil records before humans.

No formal calculations have been published since, but conservationists agree the rate of loss has increased since then, and Stuart said it was possible that the dramatic predictions of experts like the renowned Harvard biologist E O Wilson, that the rate of loss could reach 10,000 times the background rate in two decades, could be correct.

"All the evidence is he's right," said Stuart. "Some people claim it already is that ... things can only have deteriorated because of the drivers of the losses, such as habitat loss and climate change, all getting worse. But we haven't measured extinction rates again since 2004 and because our current estimates contain a tenfold range there has to be a very big deterioration or improvement to pick up a change."

Extinction is part of the constant evolution of life, and only 2-4% of the species that have ever lived on Earth are thought to be alive today. However fossil records suggest that for most of the planet's 3.5bn year history the steady rate of loss of species is thought to be about one in every million species each year.

Only 869 extinctions have been formally recorded since 1500, however, because scientists have only "described" nearly 2m of an estimated 5-30m species around the world, and only assessed the conservation status of 3% of those, the global rate of extinction is extrapolated from the rate of loss among species which are known. In this way the IUCN calculated in 2004 that the rate of loss had risen to 100-1,000 per millions species annually – a situation comparable to the five previous "mass extinctions" – the last of which was when the dinosaurs were wiped out about 65m years ago.

Critics, including The Skeptical Environmentalist author, Bjørn Lomborg, have argued that because such figures rely on so many estimates of the number of underlying species and the past rate of extinctions based on fossil records of marine animals, the huge margins for error make these figures too unreliable to form the basis of expensive conservation actions. However Stuart said that the IUCN figure was likely to be an underestimate of the problem, because scientists are very reluctant to declare species extinct even when they have sometimes not been seen for decades, and because few of the world's plants, fungi and invertebrates have yet been formally recorded and assessed.

The calculated increase in the extinction rate should also be compared to another study of thresholds of resilience for the natural world by Swedish scientists, who warned that anything over 10 times the background rate of extinction – 10 species in every million per year – was above the limit that could be tolerated if the world was to be safe for humans, said Stuart.

"No one's claiming it's as small as 10 times," he said. "There are uncertainties all the way down; the only thing we're certain about is the extent is way beyond what's natural and it's getting worse."

Many more species are "discovered" every year around the world, than are recorded extinct, but these "new" plants and animals are existing species found by humans for the first time, not newly evolved species.

In addition to extinctions, the IUCN has listed 208 species as "possibly extinct", some of which have not been seen for decades. Nearly 17,300 species are considered under threat, some in such small populations that only successful conservation action can stop them from becoming extinct in future. This includes one-in-five mammals assessed, one-in-eight birds, one-in-three amphibians, and one-in-four corals.

Later this year the Convention on Biological Diversity is expected to formally declare that the pledge by world leaders in 2002 to reduce the rate of biodiversity loss by 2010 has not been met, and to agree new, stronger targets.

Despite the worsening problem, and the increasing threat of climate change, experts stress that understanding of the problems which drive plants and animals to extinction has improved greatly, and that targeted conservation can be successful in saving species from likely extinction in the wild. This year has been declared the International Year of Biodiversity and it is also hoped that a major UN report this summer, on the economics of ecosystems and biodiversity, will encourage governments to devote more funds to conservation.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists 208 species as "possibly extinct", more than half of which are amphibians. They are defined as species which are "on the balance of evidence likely to be extinct, but for which there is a small chance that they may still be extant".

Kouprey (or Grey ox; Bos sauveli)

What: Wild cattle with horns that live in small herds

Domain: Mostly Cambodia; also Laos, Vietnam, Thailand

Population: No first-hand sightings since 1969

Main threats: hunting for meat and trade, livestock diseases and habitat destruction

Webbed-footed coqui (or stream coqui; Eleutherodactylus karlschmidti)

What: Large black frog living in mountain streams

Domain: East and west Puerto Rico

Population: Not seen since 1976

Main threats: Disease (chytridiomycosis), climate change and invasive predators

Golden coqui frog (Eleutherodactylus jasperi)

What: Small orange frog living in forest or open rocky areas

Domain: Sierra de Cayey, Puerto Rico

Population: No sightings since 1981

Main threats: Unknown but suspected habitat destruction, climate change, disease (chytridiomycosis) and invasive predators

Spix's macaw (or little blue macaw; Cyanopsitta spixii)

What: Bright blue birds with long tails and grey/white heads

Domain: Brazil

Population: The last known wild bird disappeared in 2000; there are 78 in captivity

Main threats: Destruction of the birds' favoured Tabebuia caraiba trees for nesting, and trapping

Café marron (Ramosmania rodriguesii)

What: White flowering shrub related to the coffee plant family

Domain: Island of Rodrigues, Republic of Mauritius

Population: A single wild plant is known

Main threats: Habitat loss, introduced grazing animals and alien plants

Source: IUCN and Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. To mark the International Year of Biodiversity, the IUCN is running a daily profile of a threatened species throughout 2010. See iucn.org.

It is a familiar story in the climate change debate. The US government is at odds with the rest of the world and, despite criticism, wants other countries to change their minds and fall in line behind Uncle Sam. This time, the tale comes with an unexpected twist. This weekend, the US will warn that the threat from climate change to the survival of the polar bear is so great that the world must grant it the highest possible protection.

At the meeting of the international body that regulates trade in animals, the US will push for a total ban on the sale and movement of polar bear products that are used for furs, rugs and taxidermy. Melting sea ice in the Arctic will kill thousands of bears in coming years, the US says, and continued commercial trade must not be allowed to make the situation worse. Other countries, including US neighbours and keen polar bear traders, Canada, disagree.

The US has put its proposal to the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (Cites), which meets every two-three years and tomorrow begins its 12-day meeting in Doha, Qatar. Governments from 175 countries will discuss dozens of such proposals, which could help determine the fate of, among others, elephants, tigers, rhinos and the world's dwindling stocks of bluefin tuna.

"2010 is a key year for biological diversity," said Achim Steiner, head of the United Nations Environment Programme, which runs Cites. "It is the year when the world was supposed to have reversed the rate of loss of our biodiversity. This has not happened. The international community must re-engage and renew its efforts to meet this goal. Cites is an important part of this response."

The US wants polar bears promoted to Cites appendix I, which brings an automatic ban on trade. In its proposal it says: "Sea ice changes will likely negatively impact polar bears by increasing energetic demands of seeking prey. As changes in habitat become more severe and seasonal rates of change more rapid, catastrophic mortality events that have yet to be realised on a large scale are expected to occur."

It adds: "A precautionary approach, which includes polar bears in Cites appendix I, is necessary to ensure that primarily commercial trade does not compound the threats posed to the species by loss of habitat."

Biologists reckon there are 20,000 to 25,000 polar bears in the Arctic, spread across 19 geographical sub-populations. Last year the polar bear specialist group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature said that numbers in eight of these groups were declining, three are stable and one, a group of under 300 animals around Canada's M'Clintock Channel, is increasing. The state of the other seven groups is unclear.

The US plan is backed by Egypt and Rwanda, but other nations, including Europe, are expected to vote against. Canada, which exports skins and products from about 300 polar bears legally shot each year, says the trade is insignificant compared to the threat of global warming.

The Cites meeting will also trigger a new round in a long-running debate about the sale of ivory harvested from African elephants. Trade in ivory was banned in 1989, though Cites has permitted one-off sales of government stocks from countries including Botswana, South Africa and Japan. The $20m raised from the sales were channelled towards elephant conservation, but critics say they encourage poaching and illegal trade. Tanzania and Zambia will this year push to be allowed a similar sale of ivory stocks, though other African nations such as Ghana, Kenya and Mali have signalled they will vote against the plan. All proposals need a two-thirds majority to pass.

Other Cites proposals include moves to control unregulated trade in corals and sharks, including the porbeagle, spiny dogfish and three species of hammerhead, as well as the proposed ban on bluefin tuna trade. "The marine theme of this year's Cites conference is particularly striking," said Willem Wijnstekers, Cites secretary-general. "Cites is increasingly seen as a valuable tool to achieve the target of restoring depleted fish stocks by 2015 to levels that can produce the maximum sustainable yield."

West Africa's Last Giraffes Make Surprising Comeback

A hundred years ago, West Africa's last giraffes numbered in the thousands and their habitat stretched from Senegal's Atlantic Ocean coast to Chad, in the heart of the continent. By the dawn of the 21st century, their world had shrunk to a tiny zone southeast of the capital, Niamey, stretching barely 150 miles (240 kilometers) long. Their numbers dwindled so low that in 1996, they numbered a mere 50.

Instead of disappearing as many feared, though, the giraffes have bounced miraculously back from the brink of extinction, swelling to more than 200 today. It's an unlikely boon experts credit to a combination of concerned conservationists, a government keen for revenue, and a rare harmony with villagers who have accepted their presence — for now.

By 1998, Niger's government — pressed by conservation groups — began to realize the herds were about to disappear forever. Authorities drafted new laws banning hunting and poaching. Killing a giraffe became punishable by five-year jail terms and fines amounting to hundreds of times the yearly income of farmers. The changes had a startling effect: by 2004, the herds had nearly doubled in size.

The government "realized they had an invaluable biological and tourism resource: the last population left in West Africa," said Jean-Patrick Suraud, a French scientist with the Association to Safeguard the Giraffes of Niger. The giraffes had also stumbled upon a peaceful region with enough food to sustain them, and a population that mostly left them alone. Today, they crisscross the land in harmony with turbaned nomads in worn flip-flops shepherding camels and sheep.

(unquote)

Photos courtesy of Steward Ellett / BWPA, Andy Rouse / NHPA, Rebecca Blackwell / AP, Soft European, Paul Richards / AFP, WHYY Radio, Roger Tidman / FLPA, and AnnMarie Jone / BWPA