You are hereBlogs / WcP.Observer's blog / Methane (greenhouse gas 25x potent as CO2) bubbles out 5x faster. Warmer air thaws Arctic soil, 50 bil tonnes may be released

Methane (greenhouse gas 25x potent as CO2) bubbles out 5x faster. Warmer air thaws Arctic soil, 50 bil tonnes may be released

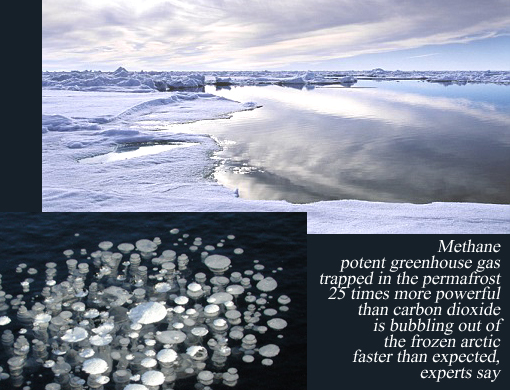

Researchers believe the Arctic Ocean seabed is thawing in patches and releasing greenhouse gases. Methane, trapped in the permafrost, 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide, is bubbling out of the frozen arctic faster than expected.

Researchers ignite a bubble of methane on Alaska’s Steward Peninsula.

Methane is leaking from the East Siberian Arctic Shelf into the atmosphere at an alarming rate. The amount leaking from this locale is comparable to all methane from rest of the world's oceans put together. Methane is a greenhouse gas more than 30 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Left: Researcher ignites a pocket of methane. Right: methane bubbles trapped in lake ice in Siberia in early autumn.

(quote)

International experts are alarmed. Methane is a greenhouse gas - 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide - that lies frozen in sediments and permafrost -- frozen soil that remains below 0°C for several years -- in arctic continental shelves. Permafrost was thought to act as a leak-proof barrier that sealed in the methane, but warming arctic temperatures are thawing the permafrost, releasing methane at a rate 5 times faster than thought. The findings are based on new, more accurate measuring techniques. Large amounts entering the atmosphere, it concluded, could lead to “abrupt changes in the climate that would likely be irreversible.” As warmer air thaws Arctic soils, as much as 50 billion metric tons of methane could be released from beneath Siberian lakes alone, according to Walter’s research. That would amount to 10 times the amount currently in the atmosphere. The amount of methane leaking from the East Siberian Arctic Shelf is comparable to all methane from rest of the world's oceans put together.

As a greenhouse gas, methane is 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide but emissions from subsea permafrost are not included in climate change prediction models.

“The sub-sea permafrost should act as a cap or seal, preventing leakage,” Natalia Shakhova, of the University of Alaska, told The Times. “Beneath it there is methane that has accumulated at high pressure. But the permafrost is losing its ability to be an impermeable cap.”

After water vapour and carbon dioxide, methane is the most significant of the gases that cause the atmosphere to retain heat. Levels have doubled since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. The permafrost that covers vast tracts of land in the far North is thawing, steadily adding methane to the atmosphere. The Arctic has warmed at about twice the rate of the rest of the planet. Climate scientists are concerned that as rising temperatures melt more permafrost, the added methane will raise temperatures further and so cause a wider thaw. “Our concern is that the sub-sea permafrost has been showing signs of destabilisation already.” The research is published in the journal Science.

The permafrost covers the Siberian continental shelf, which extends up to 1,000 kilometres into the Arctic Ocean. Dr Shakhova previously investigated methane releases from terrestrial permafrost and from northern lakes. Using Russian icebreakers to sample methane concentrations at various different water depths and above the surface at more than 5,000 locations, the team showed that methane was being released far faster than estimated.

One of the great challenges in assessing the meaning of changes in Arctic climate and other environmental conditions is putting today’s observations in long-term context. This is as true for the bubbling emissions of methane from the frozen, but warming, sea bed as for sea ice around the North Pole. Two recent studies of methane emissions from frozen sea-bed sediments, including one published in Science and described in The Times today, found substantial bubbling flows of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, were reaching the atmosphere. In its news release, the National Science Foundation, which helped underwrite the research, described the emissions as taking place “at an alarming rate.”

One thing that would help clarify Arctic trends and their causes is more monitoring of methane on the ground in and around the Arctic, Dr. Dlugokencky and other researchers say. Euan Nisbet, a University of London scientist from a team that found methane bubbling elsewhere in the Arctic, said this in an e-mail message: The Arctic is a good example of the need for “in situ” monitoring. Satellites use reflected sunlight, and so cannot see the Arctic in winter. In situ work is relatively cheap, but unloved. We need both in situ and satellite monitoring to assess greenhouse gases. The U.S. deserves a lot of credit for the superb work it does supporting in situ monitoring by NOAA, Scripps and AGAGE. He added that the European Union had canceled a project monitoring methane that was particularly valuable because it could distinguish between emissions from terrestrial bogs, gas fields and the like and ocean sources.

Four miles south of the Arctic Circle, the morning sky is streaked with apricot. Frozen rivers split the tundra of the Seward Peninsula, coiling into vast lakes. And on a silent, wind-whipped pond, a lone figure, sweating and panting, shovels snow off the ice. The young woman with curly reddish hair stops, scribbles data, snaps a photo, grabs a heavy metal pick and stabs at white orbs in the thick black ice. “Every time I see bubbles, I have the same feeling,” says Katey Walter, a University of Alaska researcher. “They are amazing and beautiful.”

Beautiful, yes. But ominous. When her pick breaks through the surface, the orbs burst with a low gurgle, spewing methane, a potent greenhouse gas that could accelerate the pace of global climate change.

International experts are alarmed. “Methane release due to thawing permafrost in the Arctic is a global warming wild card,” warned a report by the United Nations Environment Programme last year. Large amounts entering the atmosphere, it concluded, could lead to “abrupt changes in the climate that would likely be irreversible.”

Methane has at least 20 times the heat-trapping effect of an equivalent amount of carbon dioxide. As warmer air thaws Arctic soils, as much as 50 billion metric tons of methane could be released from beneath Siberian lakes alone, according to Walter’s research. That would amount to 10 times the amount currently in the atmosphere.

At 32, Walter, an aquatic ecologist, is a rising star among the thousands of scientists who are struggling to map, measure and predict climate change. According to one of her studies, methane emissions from Arctic lakes were a major contributor to a period of global warming more than 11,000 years ago. “It happened on a large scale in the past, and it could happen on a large scale in the future,” says Walter, who refers to potential methane emissions as “a time bomb.”

Methane levels in the atmosphere have tripled since preindustrial times. Human activities, including rice cultivation, cattle raising, and coal mining, account for about 70 percent of releases, according to recent studies. Natural sources, including tropical wetlands and termites, make up the rest. But those estimates had not incorporated the bubbles Walter was probing. That gas could change the entire model for predicting global warming. And lakes are not the only methane source: Newly discovered seeps— places where methane leaks to the surface—from the shallow waters of Siberia’s vast continental shelf also figure to upset previous assumptions.

Underground storage of methane is important because any sudden release of the gas in the past has largely been responsible for rapid and exponential increases in global atmospheric temperatures, has altered climatic patterns quite dramatically and has even been responsible for the mass extinction of species. Scientific researches undertaking studies have sailed the entire length of Russia’s northern coast and have discovered intense concentrations of methane that extend over several areas covering thousands of square miles of the Siberian continental shelf.

Just in the last few days, researchers have observed and recorded areas of sea foaming with gas bubbling up through methane chimneys rising from the sea bed. It is now reckoned that the sub-sea layer of permafrost, which has acted almost like a lid in preventing the methane from escaping, has melted away to allow the gas to rise from underground deposits formed before the last ice age. Essentially, if atmospheric temperatures have increased then, by definition, this must increase the temperature of water, with the resulting melting of ice that is now being observed. When water is warmed it expands, too. Hence, the rising sea levels.

Large amounts of methane are leaking into the atmosphere from a section of seafloor under the East Siberian Arctic Shelf, according to new study by an international research team. Methane is a greenhouse gas that lies frozen in sediments and permafrost -- frozen soil that remains below 0°C for several years -- in arctic continental shelves.

Permafrost was thought to act as a leak-proof barrier that sealed in the methane, but warming arctic temperatures are thawing the permafrost.

And the frozen methane is not only dissolving in the water -- it's escaping into the atmosphere. The researchers say that release of just a fraction of the methane stored in the shelf could trigger sudden climate warming.

The East Siberian Arctic Shelf covers more than 2 million square kilometers of seafloor in the Arctic Ocean. Even prior to the new study, the region was known to be a significant source of methane -- releasing 7 teragrams a year (a teragram equals about 1.1 million tons).

Previous studies in Siberia focused on methane escaping from thawing permafrost on land, but the new study went beyond the coast to offshore areas. From 2003 -- 2008, the research team embarked on annual research cruises to sample seawater at various depths; they found that more than 80% of the deep water and more than half the surface water had methane levels that were eight times greater than that of normal seawater.

Besides storing large amounts of frozen methane, the East Siberian Arctic Shelf is also very shallow, which means that methane gas doesn't have enough time to oxidize into carbon dioxide before reaching the surface. So, more methane reaches the atmosphere.

Methane release is one of the critical climate "feedbacks" that affect the entire planet's climate system as the result of a warming Arctic region.

*update Oct 24, 2012*

Climate-changing methane 'rapidly destabilizing' off East Coast, study finds A changing Gulf Stream off the East Coast has destabilized frozen methane deposits trapped under nearly 4,000 square miles of seafloor, scientists reported Wednesday. And since methane is even more potent than carbon dioxide as a global warming gas, the researchers said, any large-scale release could have significant climate impacts. Temperature changes in the Gulf Stream are "rapidly destabilizing methane hydrate along a broad swathe of the North American margin," the experts said in a study published Wednesday in the peer-reviewed journal Nature.

Using seismic records and ocean models, the team estimated that 2.5 gigatonnes of frozen methane hydrate are being destabilized and could separate into methane gas and water. It is not clear if that is happening yet, but that methane gas would have the potential to rise up through the ocean and into the atmosphere, where it would add to the greenhouse gases warming Earth. The 2.5 gigatonnes isn't enough to trigger a sudden climate shift, but the team worries that other areas around the globe might be seeing a similar destabilization.

"It is unlikely that the western North Atlantic margin is the only area experiencing changing ocean currents," they noted. "Our estimate ... may therefore represent only a fraction of the methane hydrate currently destabilizing globally." The wider destabilization evidence, co-author Ben Phrampus told NBC News, includes data from the Arctic and Alaska's northern slope in the Beaufort Sea.

And it's not just under the seafloor that methane has been locked up. Some Arctic land area are seeing permafrost thaw, which could release methane stored there as well. An expert who was not part of the study said it suggests that methane could become a bigger climate factor than carbon dioxide.

"We may approach a turning point" from a warming driven by man-made carbon dioxide to a warming driven by methane, Jurgen Mienert, the geology department chair at Norway's University of Tromso, told NBC News. "The interactions between the warming Arctic Ocean and the potentially huge methane-ice reservoirs beneath the Arctic Ocean floor point towards increasing instability."

(unquote)

Photos courtesy of Zina Deretsky / National Science Foundation, Sergey Zimov, AP Photo / Nature, Katey Walter, Getty Images, and Buffalo News

That's really very interesting post. Thanks!!

Great information posted here about Methane. Like the way you shared this post.

Is that thing real. I mean is it possible. If you are suffering from ED issues Buy https://www.royalpharmax.com/Buy-Kamagra">Kamagra 100mg.

Oh is this really the real body scanner? how would you really do that? i mean is that real? https://goo.gl/DvMPXT">OBAT WASIR de nature

Oh is this really the real body scanner? how would you really do that? i mean is that rea

Really Awesome. Technology at its best. Can't Believe that is real.