(quote)

As governments meet at the UN to negotiate towards an historic Global Ocean Treaty, a groundbreaking study by leading marine biologists has mapped out how to protect over a third of the world’s oceans by 2030, a crucial target.

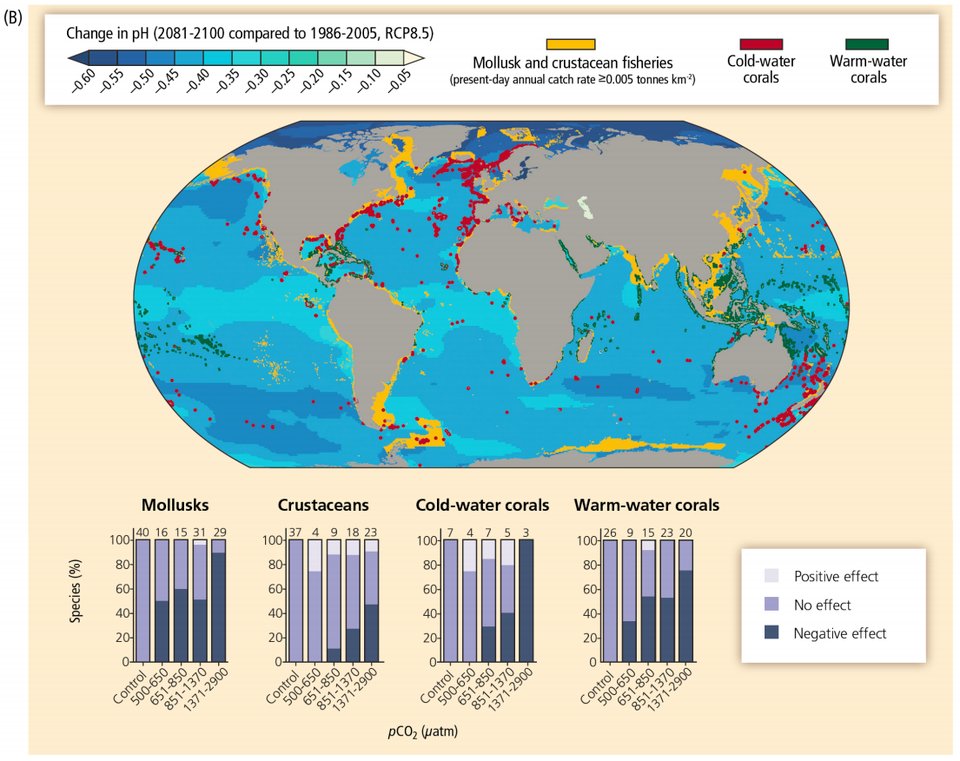

The report, 30×30: A Blueprint For Ocean Protection, is the result of a year-long collaboration between leading academics at the University of Oxford, University of York and Greenpeace. In one of the largest ever studies of its kind, researchers broke down the global oceans – which cover almost half the planet – into 25,000 squares of 100×100 km, and then mapped the distribution of 458 different conservation features, including wildlife, habitats and key oceanographic features, generating hundreds of scenarios for what a planet-wide network of ocean sanctuaries, free from harmful human activity, could look like.

The proposed network is part of a wider movement to get countries to commit to protecting 30 percent of the oceans by 2030. Governments are already working toward an international pledge to protect at least 10 percent by 2020.

The scientists released their report outlining the network on April 4, a day before the conclusion of the second round of negotiations at the United Nations toward a landmark treaty to address the ongoing decline of marine biodiversity on the high seas.

Report co-author Alex Rogers, a marine biologist at the University of Oxford, said the study puts forward the first detailed plan for a planet-wide network of marine sanctuaries. The sanctuaries would dot the globe from pole to pole, represent all marine ecosystem categories, and provide migration corridors for sea life. They would be fully protected from all human exploitation, including industrial fishing and deep-sea mining, according to the report.

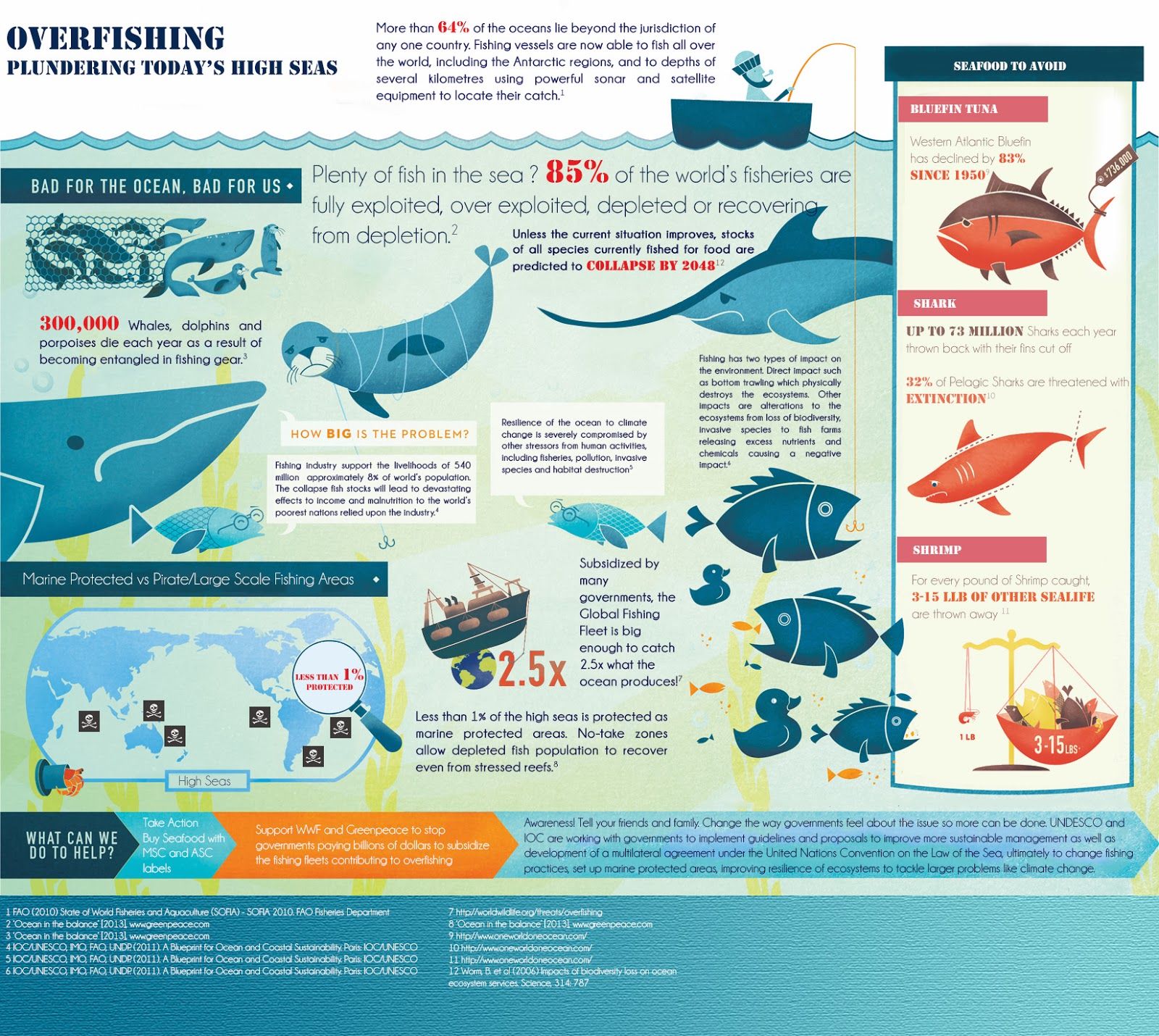

Rogers has seen firsthand the harmful effects of human activity on the otherworldly ecosystems beneath the ocean’s surface during more than 25 years exploring the deep sea and coral reefs. On expeditions to a chain of largely unexplored vents in the southwestern Indian Ocean, Rogers was struck to find the underwater mountains littered with fishing gear and ghost nets floating through the water, entangling wildlife long after they are abandoned.

“We were saddened to see the dead and dying animals trapped by those nets,” Rogers said. “It was shocking how much abandoned fishing gear [has] already gotten to these marvelous deep-sea ecosystems.”

The high seas represent about two-thirds of the world’s oceans, but they lie outside national boundaries and are not governed by any country or international body. As such, these areas lack a comprehensive oversight structure to protect the marine life that relies on them. The U.N.’s high seas treaty would create a system for coordinating the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in the high seas. It could include a mechanism for establishing various kinds of protected areas, and if so, the network outlined in the new report “shows how that could then be implemented,” Rogers said.

“I believe it is critical if we are to avoid the continuing decline of the ocean and its species leading towards a 6th global extinction event,” he added.

Aside from protecting biodiversity, creating a global network of protected areas is in all countries’ interests, according to the study authors: underwater ecosystems play an important role in mitigating climate change, with fish and squid in the sea helping to regulate carbon in the atmosphere. The animals feed on the phytoplankton that draws carbon out of the atmosphere and process it into solid feces that sink to the bottom of the sea, where the carbon remains.

(unquote)

Image courtesy blueocean.net, oneworldoneocean.com, and IPCC