(quote)

Sea Otters Returned to a Degraded Coastline Ate Enough Crabs to Restore Balance and Cut Erosion by 90%

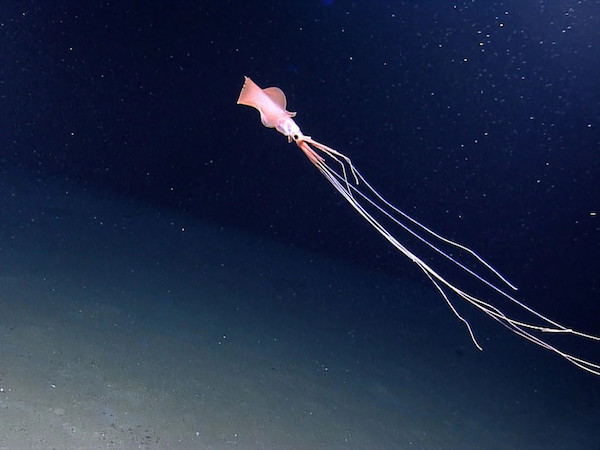

Against all odds, a distressed California coastal ecosystem is on the mend, in large part, thanks to the insatiable appetite sea otters have for crabs.

In a groundbreaking study published this week in Nature, scientists revealed that the return of sea otters to their former habitat in a Central California estuary has slowed erosion of the area’s marsh banks by up to 90%.

The resurgence of these charismatic marine mammals to the salt marshes of Elkhorn Slough in Monterey County sparks hope for improving coastal ecosystems and marks a significant ecological success story.

At a time when rising sea levels, elevated fertilizer run-off, and stronger tidal currents should be causing the opposite effect, findings show that erosion has been slashed after reintroducing a top predator—the sea otter—whose insatiable appetite for plant-eating marsh crabs is making the difference. “It would cost tens of millions of dollars for humans to rebuild these creek banks and restore these marshes. The sea otters are stabilizing them for free, in exchange for an all-you-can-eat crab feast,” said senior author and marine conservation biology professor Brian Silliman, Ph.D. at Duke University.

Like many California estuaries, Elkhorn once was a foraging habitat for sea otters, which need to eat the equivalent of about 25% of their body weight every day—around 20 to 25 pounds of food, with crabs being one of their favorite meals. But after fur traders hunted the local otter population nearly to extinction, the number of crabs exploded over the next century. Crabs eat salt marsh roots, dig into salt marsh soil, and over time can cause a salt marsh to erode and collapse.

How do otters protect salt marshes from erosion? Shellfishly

Sea otters are helping to keep the shores of a central Californian estuary from crumbling into the ocean. They act as erosion control by feasting on shore crabs — crustaceans whose burrowing and vegetation-munching habits contribute to unstable salt-marsh banks.

By the twentieth century, humans had hunted sea otters (Enhydra lutris) nearly to extinction for their fur. But conservation efforts have helped population sizes to increase, and otters are re-establishing themselves in their historical haunts, including in the salt marshes of Monterey Bay’s Elkhorn Slough. Moreover, in marsh creeks with high numbers of sea otters, erosion rates are lower than when there were fewer sea otters, researchers report today in Nature. “It’s remarkable when you think about it,” says Jane Watson, a community ecologist at Vancouver Island University in Nanaimo, Canada. “You can have a single animal, the sea otter, come in and through predation actually mitigate the effects of erosion.”

Sea otters’ love of crabs gives salt marshes a second chance

“It would cost millions of dollars for humans to rebuild these creek banks and restore these marshes,” Brian Silliman says. “The sea otters are stabilizing them for free in exchange for an all-you-can-eat crab feast.”

Sea otters are making an impact as they return to the wetlands of Central California, researchers report. Remarkable changes have occurred in the landscape as these adorable animals recolonize their former habitat in the Elkhorn Slough, a salt marsh-dominated coastal estuary in Monterey County. The erosion of creek banks slowed on average by 69% after the sea otter population fully recovered at a time when rising levels, stronger tidal currents, and nutrient pollution should be causing the opposite.

California sea otters nearly went extinct. Now they’re rescuing their coastal habitat

The California sea otter, once hunted to the edge of extinction, has staged a thrilling comeback in the last century. Now, a team of scientists has discovered that the otters’ success story has led to something just as remarkable: the restoration of their declining coastal marsh habitat.

(unquote)

Image courtesy Getty Images