(quote)

A prominent educator and patron of the arts, Henry Cole travelled in the elite, social circles of early Victorian England, and had the misfortune of having too many friends. During the holiday season of 1843, those friends were causing Cole much anxiety. The problem were their letters: An old custom in England, the Christmas and New Year’s letter had received a new impetus with the recent expansion of the British postal system and the introduction of the “Penny Post,” allowing the sender to send a letter or card anywhere in the country by affixing a penny stamp to the correspondence.

Now, everybody was sending letters. Sir Cole—best remembered today as the founder of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London—was an enthusiastic supporter of the new postal system, and he enjoyed being the 1840s equivalent of an A-Lister, but he was a busy man. As he watched the stacks of unanswered correspondence he fretted over what to do. “In Victorian England, it was considered impolite not to answer mail,” says Ace Collins, author of Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas. “He had to figure out a way to respond to all of these people.”

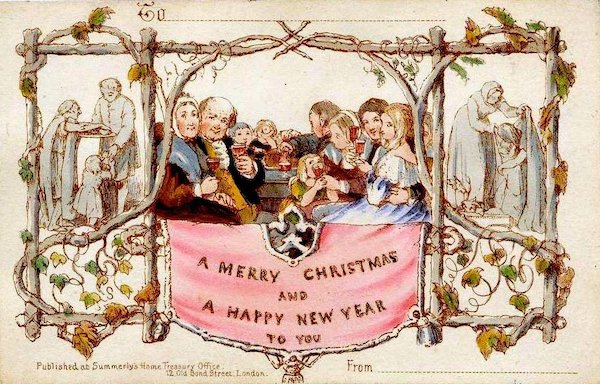

Cole hit on an ingenious idea. He approached an artist friend, J.C. Horsley, and asked him to design an idea that Cole had sketched out in his mind. Cole then took Horsley’s illustration—a triptych showing a family at table celebrating the holiday flanked by images of people helping the poor—and had a thousand copies made by a London printer. The image was printed on a piece of stiff cardboard 5 1/8 x 3 1/4 inches in size. At the top of each was the salutation, “TO:_____” allowing Cole to personalize his responses, which included the generic greeting “A Merry Christmas and A Happy New Year To You.”

It was the first Christmas card.

The modern Christmas card industry arguably began in 1915, when a Kansas City-based fledgling postcard printing company started by Joyce Hall, later to be joined by his brothers Rollie and William, published its first holiday card. The Hall Brothers company (which, a decade later, change its name to Hallmark), soon adapted a new format for the cards—4 inches wide, 6 inches high, folded once, and inserted in an envelope. “They discovered that people didn’t have enough room to write everything they wanted to say on a post card,” says Steve Doyal, vice president of public affairs for Hallmark, “but they didn’t want to write a whole letter.”

In this new “book” format—which remains the industry standard—colorful Christmas cards with red-suited Santas and brilliant stars of Bethlehem, and cheerful, if soon clichéd, messages inside, became enormously popular in the 1930s-1950s. As hunger for cards grew, Hallmark and its competitors reached out for new ideas to sell them. Commissioning famous artists to design them was one way: Hence, the creation of cards by Salvador Dali, Grandma Moses and Norman Rockwell, who designed a series of Christmas cards for Hallmark (the Rockwell cards are still reprinted every few years). (The Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art has a fascinating collection of more personal Christmas cards sent by artists including Alexander Calder.)

The unlikely Hollywood visionary of ‘Bambi’ fame designed what would become some of the most popular holiday stationery of all time

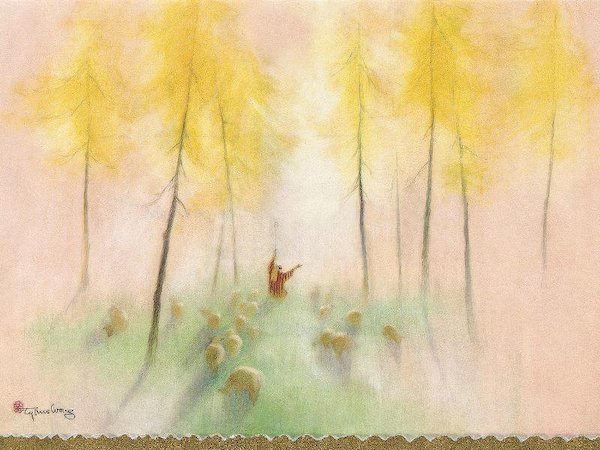

In a glass-fronted, sunlit studio on a wooded ravine in the San Fernando Valley, Tyrus Wong spent summer weekends painting Christmas imagery with a bamboo paintbrush while listening to Harry Belafonte holiday albums. From the 1950s through the ’70s, this room was where Wong designed some of America’s most popular Christmas cards, in a style that would exert a timeless appeal. Today, Wong is best remembered as a Hollywood sketch artist whose evocative scene illustrations were instrumental in the making of the beloved Disney classic Bambi. In 1954, his design of a minuscule shepherd standing under pink tree boughs while gazing at a shining star sold more than a million copies.

Wong’s talent for drawing and painting won him a scholarship to the Otis Art Institute, one of a number of art and design schools springing up in LA to train workers for the burgeoning media and entertainment industry. (Norman Rockwell would later be a visiting teacher.) Soon after his graduation in 1932, Wong became a favorite of the Los Angeles Times’ art critic Arthur Millier, who praised the “rhythmic, graceful” lines in the high-art paintings and drawings that Wong exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Fine Art and the Los Angeles Museum, among other venues. Wong’s atmospheric scene paintings—first at Disney, and then through nearly three decades at Warner Bros.—were so admired that Warner Bros. art director Leo Kuter made a point of saving his work.

Today, greeting cards are estimated to be a $7 billion to $8 billion industry, while Americans buy around 6.5 billion cards a year. Even after entering the pantheon of Disney artists, Wong always identified his card designs as the art of which he was most proud. Wong “touched lives around the world, even if people aren’t aware of it.”

(unquote)

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons and Tyrus Wong / the Hallmark Archives, Hallmark Cards, Inc., Kansas City, Missouri, USA